Thornton Marye was one of the most important architects in Atlanta and the South in the first third of the twentieth century. Not only was he a prominent architect but also a very active player in civic affairs and a pioneer in historic preservation in Georgia. So why would the buildings of such a great architect always be in the crosshairs of the wrecking ball?

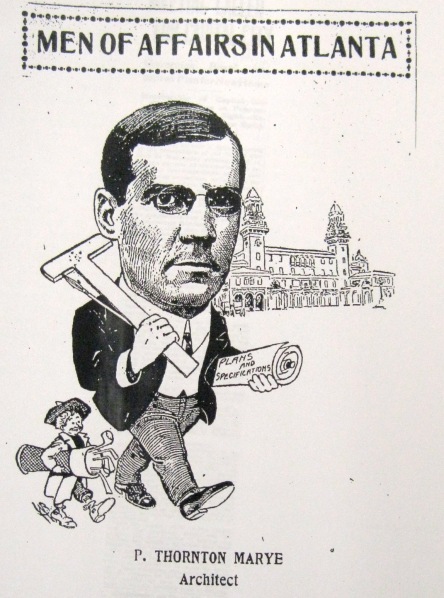

Philip Thornton Marye was born in 1872 in Alexandria. Mr. Marye attended both Randolph Macon College and the University of Virginia but learned the practice of architecture as an apprentice to Glen Brown, one of the foremost architects in Washington, D. C. In addition to practicing architecture, Brown was also very involved in restoring the original L’Enfant plan of Washington and in researching and writing about historic American architecture. Brown’s interests would have a significant impact on the young Marye.

Marye began working for Brown in 1889 and remained with him until opening his own practice in 1892 in Newport News. In 1898 Marye left to fight in the Spanish American War, serving as a captain in the Virginia Volunteers. In 1900 he married the former Florence Nisbet of Savannah, whom he met while stationed in Savannah after the war.

Marye moved to Atlanta in 1903 and became active in religious, civic, and club affairs. He was a member of the vestry of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church which he designed. He was the president of both the Lions Club and the Georgia Chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

Marye was known as quite the sportsman and was a member of the board of directors of the Capital City Club. He was also a member of the Druid Hills Golf Club, the Atlanta Athletic Club, and the Piedmont Driving Club. Marye received the highest honor afforded a Mason, the Thirty-Second degree of Masonry. Marye died of a heart attack in 1935 at the age of 63.

Because Marye’s architectural education was limited to Virginia and his apprenticeship in Washington, his military travels played an important role in supplementing his architectural education. Marye studied the Spanish Colonial architecture of Cuba during the Spanish-American War. After the war he traveled through the Caribbean and New York. In 1918 and 1919 Marye served in the American Expeditionary Force in France and Germany, and he continued to serve after the war throughout Europe. There were many comments on European architecture in his frequent correspondence with his family.

This exposure to the sophisticated and even exotic architecture of these areas insured that Marye was not simply a regional architect. How else can one explain the architect’s broad range of styles from the conservative Randolph-Lucas House to the exotic Fox Theatre?

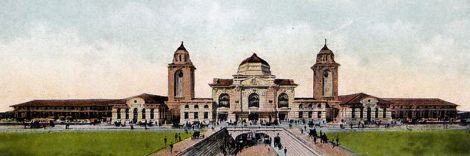

The railroad era was at its peak in the first years of the twentieth century just as Marye was designing the impressive terminals in Atlanta, Mobile, and Birmingham. These terminals were important symbols of civic pride, and the Atlanta Terminal was as important to Atlanta then as Hartsfield-Jackson Airport is today. In her thesis on Marye, Julie Morris claims, “No other buildings of that era better represented the ambitions and aspirations of American cities.” This commission alone made Marye as well known as any architect working in Atlanta at that time.

Marye’s design for the Atlanta Terminal Station beat fifteen other submissions, and the commission was so important that he closed his Virginia offices and moved to Atlanta in late 1903. Atlanta was known as “the Gateway to the South,” and the terminal building was as much an impressive entrance for the city as it was a calling card for Marye.

The Atlanta Terminal Station, completed in 1905, was also a pioneering work in reinforced concrete and established his reputation as a railroad terminal designer. After the completion of the Atlanta station, he began working for the Southern Railway Company and produced designs in Mobile and Birmingham.

While the Atlanta Terminal Station was held in high regard, the Atlanta Constitution stated, “the Birmingham Station possibly stands as the best example of Mr. Marye’s work.” The Architect and Contractor Reporter of London declared on July 30, 1910 that “the magnificent railway station [is exceptional] both for extent as an engineering problem and for the merit of its architectural design due to Mr. P. Thornton Marye, this is one of the notable railway stations in the world.”

This Atlanta landmark was demolished in 1971 and was located on the current site of the Richard B. Russell Federal Building. The Birmingham Terminal Station was also demolished in 1969, but, fortunately, the Mobile station remains.

The terminals illustrate Marye’s dexterity in adopting traditional architecture to modern technologies. He understood the complex requirements of these technologically advanced structures and was able to use the academic eclecticism of traditional architecture to create grand structures. This talent served Marye well. After the railroad boom, he would continue to earn numerous important commissions in the telephone industry throughout his career.

The Atlanta Constitution proclaimed: “In the 1920s Marye was so successful that he took on a number of partners” including the Alger brothers and Olivier Vinour. The firm became Marye, Alger, and Vinour in 1926. Marye would partner with several other architects until his death including his son, Nisbit Marye, and Warren Armistead.

Like many architects, Marye seems to have been a great networker and gained many of his clients through his social and civic activities. Marye joined the Capital City Club as soon as he moved to Atlanta, and it provided many connections for the newly arrived Virginian. Marye was able to secure several prominent residential commissions from other Virginians who had moved to Atlanta. These commissions would also provide him with another important patron, the telephone company.

In 1914 Marye designed a neo-classical house for William Thomas Gentry on East Lake Drive. The house featured a full-width, pedimented front portico and sat prominently on a small hill. Gentry, an executive with the Bell Company in Virginia, had moved to Atlanta in 1884 when he was transferred to manage the Atlanta exchange.

Also in 1914 Marye designed a house for J. Epps Brown that once stood at 2702 Peachtree Road at the southwest corner of West Wesley Road. J. Epps Brown, who had also recently moved from Virginia, joined the Capital City Club the same year as Marye. Brown, in addition to becoming the club’s president in 1914, was also the President and Chairman of the Board of Southern Bell. Epps not only hired Marye to design his house on Peachtree Road, but also the Southern Bell Company hired Marye and his partners to design many buildings throughout the Southeast. Unfortunately, this elegant Tudor house was demolished to build the “Two West Wesley Town Homes” in the 1980s.

The Southern Bell Building (1927-29) is an Atlanta art deco landmark and was once considered the city’s first modern skyscraper. Marye’s partner, Olivier Vinour, is primarily credited for the design, but the commission undoubtedly came from the long relationship created by Marye. Marye, Alger, and Vinour would also begin to design their most recognized Atlanta building, the Shrine Temple Mosque, commonly known as the Fox Theatre. The Fox Theatre would also become the rallying point for Atlanta preservationists when it was threatened by demolition in the 1970s.

Unfortunately, Atlanta has not learned from its past mistakes! While the Fox Theatre was saved, a demolition permit for another Marye design, the lone survivor of the elegant residences that once lined Peachtree Road, was issued in November 2012. Marye’s client was Hollins Nicholas Randolph, a prominent attorney, who had been practicing in Atlanta since 1896. Like Marye, Randolph was also from a prominent Virginia family. Randolph’s great grandfather had been Governor of Virginia and his great-great grandfather was Thomas Jefferson. The 1924 design of this Georgian home was based upon the ancestral home “Dunlora” in Albemarle County, Virginia where Randolph was born in 1872. The Hollins family lived in the house for ten years. Mrs. Margaret Lucas whose husband, Arthur, owned several Atlanta theatres, lived there for many years.

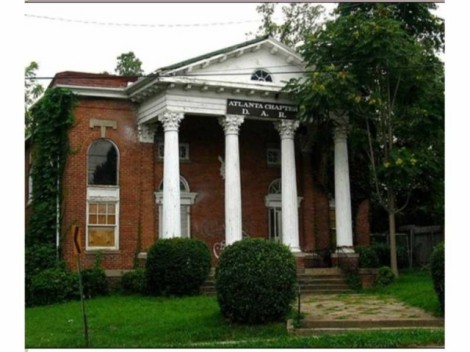

In addition to his successful practice of architecture, Marye was a pioneer in historic preservation, and it is a cruel twist of fate that so many of his works have been demolished or are currently threatened. The Randolph-Lucas House has been threatened with demolition three times since 1997. The DAR Hall on Piedmont Avenue has also been listed as one of the Georgia Trust’s “Places in Peril.”

During the Great Depression there was little or no work for architects, and the Federal Government came to the rescue by calling for measured drawings of certain historic buildings as a form of insurance against loss of data through future destruction and as a contribution to the study of historic architecture. Marye directed this work in Georgia, supervising thirty-six men. Marye’s research would have made him the foremost expert on historic Georgia architecture of his day. He helped document and research these buildings and then did a large number of reconstructive sketches of Georgia’s earliest buildings. Marye later helped illustrate two important books written and edited by his wife, Garden History of Georgia (1933) and Georgia Scenes from Log Home to Mansion. Both are very important reference materials for Georgia’s architectural and landscape history.

At the time of his death in 1935, Marye was roundly praised for his cultural contributions. One editor wrote, “First of all a gentleman, he did most for those whose lives he touched by being simply and modestly himself.” All of us in Atlanta have been touched by Marye’s work, and we are charged with doing more to preserve his legacy.

Copyright 2013 – Wright Marshall